Last Tuesday, March 8, was International Women’s Day. It seemed to get a lot of press–perhaps because it was the centenary celebration. That morning, when I opened up my e-mail and Facebook page, I was flooded with all sorts of interesting messages in honour of the day. Each day since then, I’ve stumbled across International Women’s Day related media every time I sit down at my computer.

First, both a friend and Brightwide (makers of social and political films) sent me a link to the short piece EQUALS, with Judi Dench and Daniel Craig reprising their James Bond roles. One of their many staggering statistics is the fact that women are responsible for two-thirds of the work worldwide, but earn only 10% of the income and own only 1% of the property.

Then Doctors Without Borders directed me to an article in the Huffington post on Fistual: a Horrifying Condition Affecting Women Worldwide. Caused by complications of childbirth, fistula is not a disease, but a preventable medical condition. It is a public health issue that scars women in impoverished areas of the world, particularly Africa and Asia, forcing them into lives of shame and despair. Women who suffer from this lead lives of isolation and are unable to work outside the home.

On a happier note, I also got a message from Ten Thousand Villages, a not-for-profit program that creates “opportunities for artisans in developing countries to earn income by bringing their products and stories to our markets through long-term fair trading relationships.” I drooled over all the great products made by women from all over the globe, and felt that perhaps there is something possible beyond “shame and despair.” The key here, once again, is clearly gainful employment.

The United Nations’ theme for this International Women’s Day is Equal Access to Education, Training, and Science & Technology: Pathway to decent work for women. Which brings me to the second part of my title, women writers. Well, one woman writer; South African Sindiwe Magona, to be exact. I’m currently reading Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night, which is a collection of her short stories. The first part is a series of interconnected stories that tell the experiences of various African women working as maids for white people. These stories were striking, and especially pertinent to this theme of “decent work.” Through her characters, Magona shows how domestic labour can be little better than slavery, and how it certainly doesn’t qualify as “decent work.” I’ve been thinking about this, and Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night, all week. In my opinion, the sign of a great book is one that stays with you, and makes you think.

I’d like to say more about Sindiwe Magona’s book, but I will make myself stop here as I will be reviewing it for a future issue of Belletrista. Stay tuned for more.

novel Breath, Eyes, Memory, published in 1994 (it was chosen for the Oprah Book Club four years later). The book tackles race and gender issues in a way that reminds me of Toni Morrison, one of my favourite writers. Danticat’s writing is uncomplicated but evocative and she doesn’t flinch from showing how women are subjected to distress and pain.

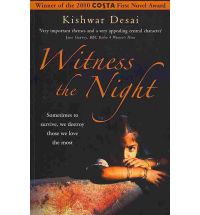

novel Breath, Eyes, Memory, published in 1994 (it was chosen for the Oprah Book Club four years later). The book tackles race and gender issues in a way that reminds me of Toni Morrison, one of my favourite writers. Danticat’s writing is uncomplicated but evocative and she doesn’t flinch from showing how women are subjected to distress and pain. Last week I read an excellent book called Witness the Night, by Kishwar Desai. Set in 21st century India, it’s part murder mystery, part social critique. Instead of a police detective, the sleuth in this story is an unconventional social worker who gets herself involved in a wealthy family’s attempt to promote an all-male progeny. I had the good fortune to have the opportunity to read this novel for the next edition of Belletrista.

Last week I read an excellent book called Witness the Night, by Kishwar Desai. Set in 21st century India, it’s part murder mystery, part social critique. Instead of a police detective, the sleuth in this story is an unconventional social worker who gets herself involved in a wealthy family’s attempt to promote an all-male progeny. I had the good fortune to have the opportunity to read this novel for the next edition of Belletrista.